Wallace’s skill as a scientist is his affinity “not for looking, exactly, so much as it is for waiting,” for waiting “like a savant or a trained circus seal” for his instruments to take their measurements. Do you understand that? It’s real life.” In Real Life, Wallace’s feelings are choked away behind piles of detached observations Wallace’s problems at school, some of his friends tell him, are not meaningful because school is not “real life” moreover, his anger when one of his friends tells the rest about Wallace’s dead father without telling Wallace first is “selfish.” But his betrayal of his friends’ confidences does matter because, his friend Vincent says, “this is real life, Wallace.

And as tension within his group rises, the idea of “real life” becomes a weapon that its members bat around at each other. Wallace begins to lash out at his friends, spilling confidential secrets at a dinner party. “I fucking hate it everywhere.” But he sees no alternatives: “I don’t know where to go or what to do.” Vox-mark vox-mark vox-mark vox-mark vox-mark His classmates keep implying that he’s only in the program at all because of affirmative action. His supervisor, who keeps telling Wallace that his work is not up to par and that she cannot have a misogynist in her lab, is of no help. He suspects sabotage from the racist and homophobic labmate who has accused him of misogyny. His abusive father has died and Wallace has missed the funeral, and more urgently, his nematodes have been corrupted, wasting his summer’s work. He refers to his friends as “his particular group of white people.” The town locals he calls “real people,” and he is amazed at “how quickly he has forgotten to move among such people, who seem rough and ugly when they look at him.”

On the other hand, Wallace is deeply aware of how white and how sheltered the university is, and he has a sense that this quality makes it unreal. When the only member of his friend group who is not a student says, “There’s more to life than programs and jobs,” Wallace replies, “I’m not entirely sure that’s true.” He believes he has entirely discarded his past, his desperately unhappy childhood as a queer black kid in the rural south, so that now, with “his previous life cut away like a cataract,” he has rendered it no longer real. It consumes his time, his energy, his attention: All he does is sit in the lab behind his microscope, studying nematodes.

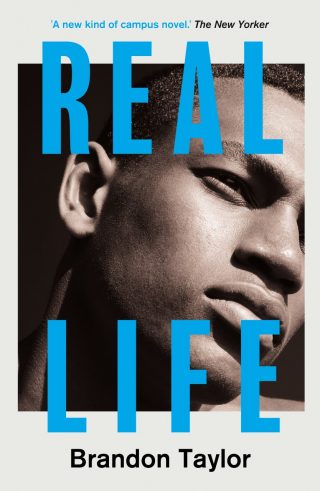

On the one hand, Wallace is devoted to his program, in which he is the only black student to enroll in the past three decades. Our protagonist, Wallace, is a grad student studying biochemistry at a university in the Midwest, and he is ambivalent as to whether his life as a student could be said to constitute “real life.” The central question of Real Life, the debut novel from short story writer and Iowa MFA grad Brandon Taylor, is: What is real life?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)